Steam Condensation as a Food Decontamination Method

Table of Contents

Pressurized Steam Decontamination

Atmospheric Steam Decontamination

Sub Atmospheric Steam Decontamination

Microwave Decontamination

Decontamination of Heat Sensitive Products

Ozone Decontamination

Comparison of Different Treatments

Research being conducted at the UK's Food Refrigeration and Process Engineering Research Center (frperc), University of Bristol, is looking at the potential of steam condensation at, above and below atmospheric pressure as a decontamination method for red and white meat, meat products, vegetables, herbs and fruit. The synergistic effect of adding organic acid to sub atmospheric steam is also being evaluated. Comparative studies have also been made using hot air, water immersion, infrared, microwaves and ozone.

An effective three-stage research strategy has been developed for this research program:

• Experimentally determine the limiting conditions in terms of changes in appearance and texture.

• Use mathematical modeling to determine treatments within the quality limitations most likely to maximize bacterial reduction.

• Experimentally test those treatments using naturally contaminated and inoculated food samples.

Pressurized Steam Decontamination

Very high rates of temperature rise at the surface of samples can be achieved by condensing steam under pressure. Surface cooking can be avoided by immediately vacuum cooling after treatment.

The initial pressurized steam decontamination rig at frperc consisted of a 1 m long by 0.6 m diameter steel process vessel, a steam generator and vacuum pump protected by a condenser chamber (see figure 1).

After the food is loaded the operating cycle has three phases:

• A vacuum is drawn to remove non-condensable gases.

• Steam is introduced to rapidly increase the surface temperature of the food.

• The food is rapidly vacuum cooled

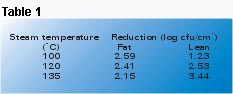

The pilot plant has been used to investigate the decontamination of peppers, soft fruit, poultry, red meat primals and consumer cuts. Studies on decontaminating beef showed no systematic difference between reductions produced on fat or lean surfaces (see table 1). On the surface of fat the reductions were not influenced by steam temperature while those on lean significantly increased with increase in steam temperature.

There is a marked difference in the ability of the outer and cut surfaces of beef muscle to withstand heat treatments without changes in their appearance.

The plant has now been extensively modified to minimize the duration of the decontamination cycle.

Atmospheric Steam Decontamination

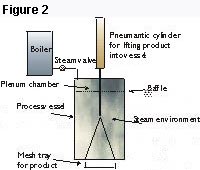

Any pressurized steam/vacuum cooling system is likely to be expensive and be difficult to automate. An atmospheric steam plant has a much simpler design (see figure 2) and mode of operation. In such a pilot plant developed at Langford, steam is continuously fed into the top of a vessel with an open bottom. As the steam fills the vessel, it displaces any air and since it is lighter than air it remains in the vessel with a slight spillage from the open bottom. The food to be decontaminated is inserted though the open bottom. After a set exposure time it is removed and immediately cooled. Initial prototypes were constructed from barrels used for transporting fruit juice. A food grade stainless steel system has now been commissioned for industrial trials.

Investigations have been carried out on the decontamination of lamb carcasses, red meat cuts, whole poultry and poultry portions, soft fruits, peppers and herbs.

Investigations have revealed a marked difference in the ability of the outer and cut surfaces of beef muscle to withstand heat treatments without changes to appearance (see table 2). Chilled soft fruit, raspberries and blackberries, were very successfully decontaminated in the atmospheric steam decontamination plant. Initial contamination levels of typically 103 to 105/g were consistently reduced to below the level of detection of 20/g.

Sub Atmospheric Steam Decontamination

With heat sensitive foods decontamination may have to be carried out at temperatures lower than 100°C. Sub atmospheric steam decontamination systems are therefore under investigation.

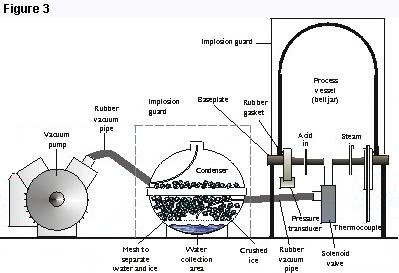

In operation the sample of the product to be decontaminated is suspended from a rack. The process vessel (approximately 0.45 m high by 0.3 m diameter is placed over the rack. The vessel is then evacuated to remove non-condensable gases. Steam is introduced and the desired temperature maintained by controlling the vacuum pressure within the vessel. After the desired treatment time has been reached the steam is shut off and vacuum cooling applied. Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the test apparatus.

Additional operations were carried out when the synergistic effect of adding organic acid to sub atmospheric steam was evaluated. A set amount of organic acid at the desired concentration was sprayed onto the surface of the product. In different trials the acid was sprayed before or after steam treatments and different residence times were also employed.

Investigations on the decontamination of beef (lean and fat), poultry (skin on and skin off), paté, pig skin, peppers, apples and lettuce have been carried out in the sub atmospheric steam pilot plant.

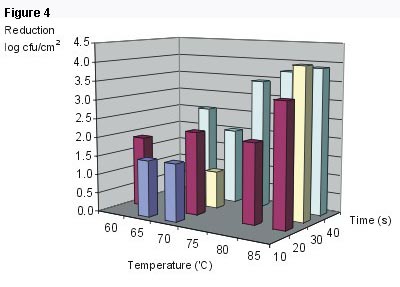

Results (see figure 4) show that there is a strong trend for the magnitude of bacterial reduction to increase with both steam temperature and exposure time. Reductions of approaching 2 log10 cfu/cm² have been measured after a 10 s exposure to steam at 65°C. After 40 s exposure at temperatures of 80 or 85°C, reductions approached 4 log10 cfu/cm². The initial indications are that using organic acid sprays in conjunction with the condensing steam can produce a small additional reduction in bacterial numbers.

Microwave heating can produce very rapid increases in surface temperature and therefore has the potential to decontaminate foods. However, heating poultry carcasses or portions at full power in a domestic oven results in:

• Considerable variability, up to 30°C, in final surface temperatures at the same defined positions on replicate carcasses,

• An average temperature difference of up to 61°C between different points on the carcass.

Conditions could not therefore be found that could guarantee substantial reductions in surface pathogens without causing substantial protein denaturation (cooking) of the chicken.

Heating on reduced power for longer times and shielding extremities of the carcass made some improvement to the temperature distribution. However, the improvement would still not achieve consistent reductions in pathogen numbers without substantial cooking.

Heating specially shielded slabs of chicken breast on top of a microwave absorber in a controlled microwave cavity produced more repeatable heating and an average temperature distribution of 58 to 62°C. However, substantial protein denaturation (cooking) of the chicken was still observed and such a process is unlikely to have an industrial application.

Decontamination of Heat Sensitive Products

None of the heat based decontamination processes have proved suitable for leafy salads, such as lettuce, or herbs.

A limited trial has been carried out on the use of ultra-violet (UV) light for decontamination of food products. Initial trials on the effect of exposure to UV light have been performed in conjunction with Laser Installations Ltd of Scotland. A UV source was positioned 150 mm above a working surface and chicken, beef and lettuce were exposed to ascertain the time until damage occurred. Damage was subjectively assessed by a panel of judges in terms of visually detectable change from the raw product. Iceberg lettuce showed the best resistance to damage by UV light.

Monitoring the reductions of total viable counts and numbers of E.coli on inoculated samples assessed the effect of UV on surface bacteria. Experimental treatment exposure times were 1/3, 2/3 and full maximum resistance times. The bacterial reductions showed significant variation and no apparent correlation to exposure time. Reductions of greater than 2 log10 cfu/cm² were achieved with Iceberg lettuce. This was better than results for all other products.

Overall, the levels of reduction were comparable with other methods investigated at Langford but the good results for Iceberg lettuce suggested that exposure to UV light may have potential for decontamination of certain leafy products.

Foods such as herbs and leafy vegetables pose particular problems regarding decontamination. Studies at frperc have shown that many of these foods are so fragile that steam and heat decontamination techniques are unacceptable. For these foods the application of chemicals such as ozone, or non-thermal treatments would seem to offer the best potential.

Ozone is one chemical under investigation at Langford. Ozone is a water-soluble naturally occurring gas, which is a powerful oxidizing agent. It is widely used to treat water. Ozonated water has been studied for decontaminating meat and vegetables. Gaseous ozone has long been used to control the growth of microorganisms on meat, fruit, cheese and other products during refrigerated storage with varying success. The use of gaseous ozone to directly treat (decontaminate) food products has been less common.

A recently completed student project at frperc, using equipment provided by Ozone Industries, indicated that substantial bacterial reductions can be achieved on vegetables and herbs without appreciable damage, by exposing them to high levels of gaseous ozone for relatively short periods of time. Ozone treatment extended the shelf life of products such as tomatoes, peppers and parsley by as much as 2 days.

At Langford we are also becoming interested in the use of gaseous ozone to disinfect food-processing areas. The few studies made in this area indicate that ozone has considerable potential as a disinfectant for food processing areas. It offers a number of advantages compared with conventional chemical fogging, such as convenience, lack of residues, reduced inhalation of disinfectant by staff and rapid dissociation of gas after use. It is also equally effective on both horizontal and vertical surfaces unlike chemical fogging which is more effective on horizontal surfaces.

Comparison of Different Treatments

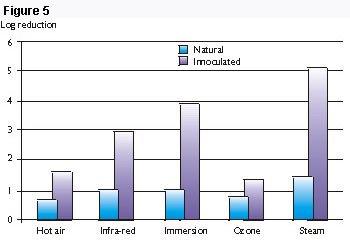

Studies on the decontamination of green peppers compared steam under pressure with other heat treatments and ozone. Steam treatments resulted in higher bacterial reductions from both inoculated and naturally contaminated surfaces (see figure 5) than any of the other treatments.

Further studies have used steam and hot air to produce heating and cooling cycles that could be expected to result in very large (>7 log10 cfu/cm²) reductions in the numbers of bacteria on the surfaces of peppers. The peppers were inoculated with 5 to 6 log10/cm² E. coli O80 and bacterial reductions measured using surface swabbing and homogenized sample techniques.

In other trials, lamb carcasses were decontaminated immediately after slaughter using either immersion in hot water, with and without chlorine, or atmospheric steam. All three treatments resulted in low levels of bacteria. After 24 hours in a chill room the treated carcasses were indistinguishable from untreated controls.

The Food Refrigeration and Process Engineering Research Center was formed as a new Research Center within the University of Bristol in January 1991. frperc is a multi-disciplinary group which consists of 12 research workers. The history of the group spans over three decades; initially as part of the Meat Research Institute and later as the Food Research Institute.

Food Refrigeration and Process Engineering Research Centre (frperc), University of Bristol, Churchill Building, Langford, Bristol, BS40 5DU, UK. Tel : +44 (0)117 928 9239; Fax : +44 (0)117 928 9314. http://www.fen.bris.ac.uk/faculty/frperc/frperc.htm